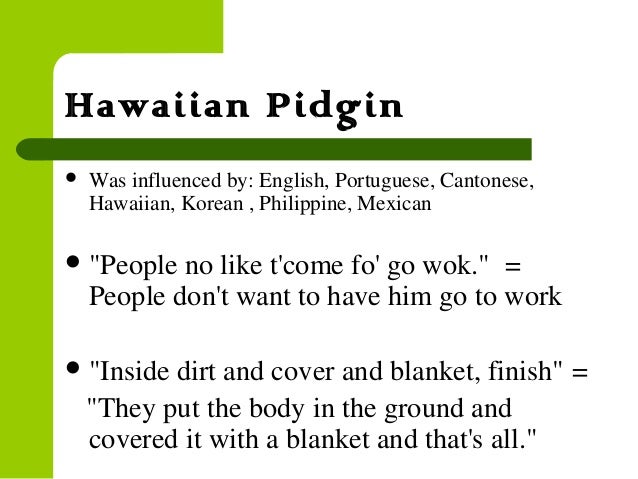

This article examines the role of orthography in the standardization of pidgins and creoles with particular reference to Pidgin in Hawai'i. The analysis shows that Jong’s text contains a mixture of features from CPE and other pidgins, as well as features of interlanguage, including some resulting from functional transfer from Jong’s first language, Cantonese. Still other features have not been recorded for any pidgin, such as the use of been as a locative copula. On the other hand, some features are more characteristic of Australian or Pacific pidgins - for example, the use of belong in possessive constructions. Some features are typical only of CPE, such as the use of my as the first person pronoun. The main part of the article examines the linguistic features of CPE and other pidgins that are present in the notebook, and discusses other lexical and morphosyntactic features of the text. It goes on to describe Jong’s notebook and the circumstances that led to him writing it. The article presents some background information about Chinese immigrants in the region where Jong worked (Victoria), and evidence that some CPE was spoken there. This article describes a recently discovered source that throws light on the nature of CPE used in Australia during that period - a 70 page notebook written in a form of English by a Chinese gold miner, Jong Ah Siug. Most of them originated from the Canton region of China (now Guangdong), where Chinese Pidgin English (CPE) was an important trading language. More than 38,000 Chinese came to Australia to prospect for gold in the second half of the 19th century. It is argued that there was some transmission of the use of for in these pidgins to the for in creoles. The use of for in the pidgin is compared with similar lexical items in four other pidgins. In this Basque Pidgin, twelve of the fifteen sentences contain the lexical item for in diverse functions. Third, in the current debate on the origin of fu and similar markers as complementizers, many claims have been made. It is suggested that the knowledge of an English Nautical Pidgin played a role in the formation of this pidgin. Second, although the sentences come from a Basque word list compiled by an Icelander, there are also some words from other languages, of which English is the most prominent.

First, Basque may throw an interesting light on the pidginization process because it is not an Indo-European language and has several unusual features. These sentences are interesting for several reasons. paper deals with a Basque Nautical Pidgin from which a number of sentences have been preserved in a seventeenth century Basque-Icelandic word list.

#Academic sources on pidgin language full

it is extended beyond the relationship between French and Kreyòl.Ĭlick below to download the full article PDF. Based in these findings, I suggest that the linguistic sociolinguistic situation of Haiti is more complex, i.e. I show that while bilingual speakers do use both Frenchification and LÃ, monolingual speakers overuse nasalization as compared to bilingual speakers, but use Frenchification less than the bilingual group because it is harder to produce.

chat lan for chat la ‘the cat’, as a feature of KS.

In this article, I establish the nasalization of the definite determiner /la/ in non-nasal environments ( LÃ), e.g. In contrast, monolingual speakers use Kreyòl rèk (KR), a variety in which Frenchified features do not generally occur ( Fattier-Thomas 1984 Valdman 2015). The Haitian Creole (Kreyòl) spoken by bilingual speakers is a prestigious form of speech generally referred to as Kreyòl swa (KS), where Frenchified features (e.g. Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages, 37(2). On the influence of Kreyòl swa: Evidence from the nasalization of the Haitian Creole determiner /la/ in non-nasal environments.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)